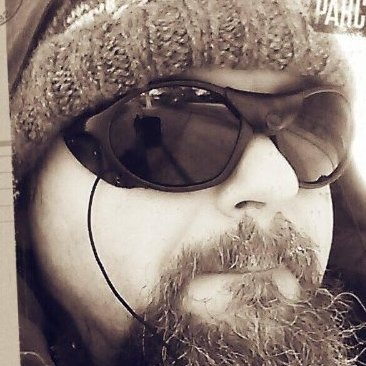

Dave Smith is with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office of Environmental Information in Washington D.C. Dave has a background of over 25 years of experience in working with geospatial technologies in applications ranging from emergency response and field data collection to modeling, analysis, and web mapping. Dave is also a licensed civil engineer and professional land surveyor, where he also worked on writing code and practical applications of using computers to automate data analysis and design. He is currently working with EPA’s Chief Data Scientist Robin Thottungal on building out a big data analytics cluster to improve EPA’s analytical capabilities.

Outside of the office, Dave has done a lot of volunteer work with various organizations, having been a top contributor to OpenStreetMap, aiding rescue and rebuilding efforts after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, as well as supporting organizations like Red Cross, U.S. State Department, and Team Rubicon in humanitarian and disaster relief mapping. Prior to that, Dave also volunteered his engineering and geospatial knowledge to support Engineers Without Borders on potable water and sanitation infrastructure for communities in Cameroon, Honduras, Rwanda and other communities in need.

You can find Dave on Twitter at @DruidSmith and on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/in/davidgsmith

Dave was interviewed for GeoHipster by Atanas Entchev.

Q: How did you get into GIS?

A: Maybe I was born to map. As a kid I grew up reading books such as Lord of the Rings and loved Tolkien’s hand-drawn maps. I started emulating his maps, creating my own maps of the locales in the fantasy and sci-fi books that I would read. You could say mapping was ingrained in me even as a pre-teen and then continued to weave its way through my life.

As a kid we lived in Germany for 10 years, and I was into scouting — I participated in both the German Pfadfinderschaft and a U.S. military-based Boy Scout troop in Germany where we would do orienteering, hiking, camping, and other activities with these wonderfully detailed, large-scale German topographic maps. These maps were essentially their version of our USGS topo quads, which had the funny-sounding name of “Messtischblatt”, as they were originally created with an alidade and plane table (“Messtisch” meaning “measuring table”) and compiled into a published map sheet (the “Blatt”).

Those scouting activities introduced me to more robust concepts like map scale and symbology, for example: differing symbols for hardwood versus pine forests, or contours and hachures to represent terrain. I started incorporating some of those concepts into the maps I would create for the fantasy realms I was reading about in my favorite books at the time. I first got into digital mapping while surveying in high school, with my first exposure to what we think of as GIS today being ARC/INFO in college.

Q: You are a licensed land surveyor and professional engineer. Do you feel that the career move to GIS was a step up from engineering and surveying? Why / why not?

A: Wow, picking between careers feels like asking a mom which is her favorite child. On the other hand, did I really ever leave one discipline for the other? In my case, the various disciplines I’ve been involved in seem to have merged and morphed, with various threads from academic and work pursuits becoming interwoven. I’ve tried steering myself toward the Venn diagram of intersecting circles of “things you enjoy” versus “things you are good at” and “things you can make a living at” to find the sweet spot where they intersect. Over time, I’ve found myself in that sweet spot.

When we moved back to the U.S. I was a teenager. One year in high school I managed to get a summer job with a land surveying firm. That job was great: getting to go out into the woods with the crew, recording a bunch of measurements, and bringing that data back into the office, reducing the notes and using the calcs to create maps. Plus, it was better money and less messy than washing dishes, landscaping, painting houses, or other summer jobs I had been doing. So, I was already a “professional mapper” when I was still in high school. It helped with school too, as I was taught about the techniques and how to do the math, which turned me into a trigonometry ninja. And, later on it helped with some of my college expenses too.

When I first started working in surveying, the company was a small mom-and-pop outfit founded in 1959. They were old school, hand-drafting maps and using transits and programmable HP calculators. Since I had taken drafting in high school they let me test my chops at drawing maps. I found myself already taking shape as a young geohipster, occasionally exercising my artistic side with artisanal hand-drawn north arrows and other creative design elements. A bit later we were in a building boom and needed to modernize to keep up. We hired additional field crews and got electronic total stations and data collectors for the field as well as computers, a plotter, and software for the office. That’s how I learned things like AutoCAD, coordinate geometry software, and digital elevation modeling. To support some of the subdivision and land development work, I also learned about stormwater runoff modeling, storm drainage, roadway design, and other civil engineering basics.

I really enjoyed working with the computers, and I taught myself how to do some automation for some of the repetitive tasks, such as LISP programming to support the CAD work, and writing code to help with many of the design calculations. At home I had a TRS-80 computer that I had saved up for and bought when I was 13. Later, in high school, I saved up and built my first homebrew PC-compatible computer from components, and was endlessly hacking around with it.

When it was time to go off to college, I still wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with myself. I started out in computer science, but became frustrated as the initial coursework seemed like a step backwards when I had already been writing code for several years. As someone interested in such a huge variety of things, whether archaeology, astronomy, or history, I changed majors several times. But I kept working summers and holidays at the surveying firm, and took surveying and civil engineering courses as those seemed a viable and responsible path for my otherwise unfocused youthful exuberance.

But one day I happily stumbled across my university’s Geography department and its GIS program, and I changed majors one final time. Here, the coursework gave me new inspirations, adding new concepts like remote sensing and satellite imagery, human geography, and interesting methodologies for analysis and spatial statistics. One of my favorite professors was Peter Gould, who taught complex statistical methods, analysis of variance, kriging, and other things; no textbook, his class was reinforced via real-world challenges and computer analyses. I recall getting something like a 43% on my first exam. Dejected, I wondered if I would make it through his class. Professor Gould walked over, patted me on the shoulder and said “great job, you got one of the top grades.” I ended up with my degree in Geography — with a specialization in Cartography, Remote Sensing, and GIS. As a student, I also got to work on some interesting projects, like working with the City of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on developing their GIS concept and framework.

The challenge of getting into GIS almost 30 years ago, however, was that GIS jobs were pretty scarce. I continued working in surveying and then various civil engineering firms, including working for some of the top engineering firms in the country. As things progressed, I gained enough experience to sit for the exams to become a Land Surveyor, and then for a Professional Engineer. In that engineering journey I ended up being appointed by Governor Rendell to the Pennsylvania Engineering Board overseeing licensure in the surveying, engineering, and geology fields. I chaired that Board for two years, and was heavily involved with NCEES and other organizations on examinations and other aspects of licensure.

In my engineering pursuits I found that civil engineering and GIS are interwoven. Engineering design depends on maps and data, and I was often called on to help out with urban and regional planning. In the early 1990s I was involved in one of the largest land use analyses east of the Mississippi. It required assembling huge amounts of data across paper maps, disparate files, and databases. This project required a lot of digitization, data optimization and management, data reprojection, and data transformation before we could even get to analysis and mapping. Nowadays the GIS kids just push a button; we old timers had to do it uphill, both ways, in 4 feet of snow – and remind me to tell you about the couple of weeks I spent surveying up on the Canadian border, waist deep in snow. At any rate, I ended up writing a bunch of homebrew GIS code to augment and extend the commercial tools we had. In the engineering world I also did a lot of work with hydrology and modeling, HEC-2 water surface profiles, transportation networks, even 3D modeling and rendering, and the worlds of engineering, GIS and code became more and more blurred over the years.

To this day I still rely on engineering principles, like solving complex technical challenges by deconstructing them into their constituent parts, trying to understand the interconnections and dependencies, and figuring out an architecture — whether hydrologic networks, transportation systems, or IT architectures, there are a lot of engineering principles and techniques for approaching them.

Q: How and why did you end up at the EPA?

A: I like to challenge myself and try new things. So, around 12 years ago, I took a big step and started a consulting at an engineering and GIS firm. Eventually, I teamed up with a guy who was also doing environmental and GIS consulting. As my partner was a disabled veteran, we structured as a Service-Connected Disabled Veteran Owned Small Business (SDVOSB), and we approached some larger government contractors about providing geospatial capabilities as a subcontractor. We quickly ended up working as a niche geospatial consultant with companies like Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, and CGI Federal on a variety of interesting projects for the military and other agencies. But because both of us were more interested in environmental protection, we put our main focus on EPA. We provided EPA with GIS support for Hurricane Katrina, and worked on many of EPA’s public-facing web mapping capabilities. While the company grew, I started to tire from the challenges of running a small business; the feast and famine cycles, writing endless proposals, and bouncing from customer to customer, when I really wanted to focus most on supporting a mission around using GIS to understand our environment and help protect it.

During the course of our EPA contracting, I learned that an EPA colleague was retiring. He had been managing EPA’s Facility Registry Service, which integrates and conflates geospatial data from many systems for millions of facilities and sites, and which serves as a geospatial underpinning for a lot of what EPA does. I knew the system well, and when the job announcement came out, I applied and got an offer.

Since then, I’ve been innovating with EPA. Here, I work with groups like the Homeland Infrastructure Foundation Level Data Workgroup (HIFLD) to provide new datasets to support emergency response. I cut costs through automation, improve match logic, and develop web services, including a reusable widget for reporting applications. The widget retrieves and prepopulates information, it validates, standardizes, and geocodes locations. It also allows users to fine-tune the location via a web map. It has since been deployed to a half dozen reporting systems, improved data quality at the source, and helped reduce burden significantly (140,000 hours of annual burden in one program).

Q: What do you do for the EPA? What kind of role does GIS play in supporting EPA in its mission?

A: At EPA we recently created a data analytics division, and hired a Chief Data Scientist. I now work for the Chief Data Scientist, Robin Thottungal, pursuing not only geospatial tech but also big data, machine learning, and other types of analytics. Currently I’m building cloud-based infrastructure to support distributed computing using Apache Spark and other technologies. We’re interested in offloading some of our geoprocessing and analysis to the cloud, along with better leveraging external data sources and emergent technologies for analysis. I’m also looking at how we can handle sensor data more robustly, and how to apply remote sensing for a variety of applications such as detection of Harmful Algal Blooms.

EPA’s mission is to protect human health and the environment. That covers broad territory, whether Emergency Support Function 10 and responding to oil or hazardous materials releases after a disaster, remediating a contaminated former industrial site, or assessing water quality. Environment is all about place, and so much of what we do has that spatial component. GIS is a core piece of support infrastructure at EPA, we have great GIS people across the agency. We’ve had a robust GIS workgroup for well over 20 years, and have had a Geospatial Information Officer for over 10 years. Our people are improving how we collect GIS data in the field, conducting advanced modeling and analysis, and expanding the use of mapping across the agency. We also train with the intent of democratizing technology across the agency, making it easier for non-technical users to map and visualize their data.

Q: What kind of technology do you use at work?

A: It’s quite a laundry list — for desktop mapping I’ve largely transitioned over to ArcGIS Pro, which is great if you already have nice clean data. I use SQL, R, Python, OGR/GDAL and others for data crunching and data prep tasks. A lot of our current infrastructure is Esri-based, with Oracle Spatial on the back end. However, I’ve found that database licensing constraints often lead to enterprise servers that are used for too many competing purposes, whether as a transactional system, data warehouse, or other functions stacked on top of each other. This means that it’s hard to optimize to do any of those jobs well, so I’ve been taking a step back, offloading, decoupling and leveraging more open source, like PostgreSQL and PostGIS, along with other open source technologies. I also do occasional lightweight work using Leaflet and various JavaScript frameworks. Recently we’ve added some point-and-click data viz tools like Qlik Sense for building dashboards, interactive charts, and graphs.

But we’re also looking at how to handle streaming data, big data, and distributed computing clusters — so I’ve started to experiment with an Apache Spark cluster on Mesos, along with Elasticsearch and other technologies that can bring us scale. As we look at deploying in the cloud, I’ve been delving into Docker as a means of containerizing, deploying, and managing our infrastructure in a replicable, maintainable, and cloud-agnostic way. We are working in a test environment in Amazon Web Services (AWS) with our eye on production, one of the big pieces being putting together the Authorization to Operate (ATO) documentation for the AWS environment. I also deployed JupyterHub in our test environment in AWS, which allows a user to create notebooks containing executable code (Python, R, Julia and others) along with annotation, embedded graphics, and other capabilities, with an eye toward supporting some of our scientific computing needs for more technical users in a self-service way. Esri recently rolled out their Python API that enables Jupyter-based approaches. Our little team is also digging into machine learning and analysis in the test Jupyter environment.

Q: Tell us about some of the cool projects you are working on.

A: Aside from building out some cool new infrastructure in the cloud, I get to tinker with a pretty wide variety of projects. For example, I recently built a tool to visualize streaming water sensor data, using Open Geospatial Consortium sensor standards. The tool allows users to slice and dice the data temporally; almost immediately we detected a recurrent anomaly in the data that the sensor operator hadn’t previously detected. Additionally, it provides dynamic, interactive ways to look at relationships between different sensor parameters, such as suspended solids, nitrates, and e. coli concentrations. I’d love to be able to set that up so that it can traverse upstream or downstream, pulling in other related sensor data from the stream network, since the devices are now all spatially indexed to the National Hydrology Dataset (NHD). I’ve also been building out tools that provide better insight on environmental impacts affecting tribes and American Indian country, using a combination of spatial queries and other approaches.

Q: You ride a bike and like craft brews — two mandatory geohipster attributes. Do you have any other?

A: For the male geohipsters, I possess an epic beard, however I’ll pass on the waxed handlebar mustache. And for the foodie geohipsters, I’ve brewed my own beers, I make things like pickled daikon, homemade mustard, gochujang chicken and Thai curry, and while I have been known to eat hipster foods like kale and quinoa, you won’t find me washing it down with a can of PBR. And I definitely have hipsterishly eclectic music tastes, ranging from funk to punk, blues to ska, a lot of artists not well known in the mainstream. I do actually own vinyl discs and a turntable, but I confess: most of what I listen to is digital.

But to get serious, I’ve noticed that the real geohipster attribute is to be innovators, makers, creators with broad interests and backgrounds. I came from a creative and resourceful “maker” family. When my parents settled in Pennsylvania, I was a nerdy city kid – born in Massachusetts, spent most of my childhood in Germany, then to El Paso, Texas. As I grew up, I became a country kid on a hundred-acre farm in the wooded Pocono mountains of Pennsylvania. There we raised goats, sheep, chickens, and other animals. We had a huge garden and did a lot of canning. We would hunt and fish, and were pretty self-sufficient. My mom and stepdad make a great team. She is a very talented sculptor and painter, and he is incredible at woodworking. She spins and weaves with their sheep’s wool, and he researches and rebuilds damaged antique spinning wheels using his lathe. My mom, with her undergrad in Chemistry and grad work in Germanic languages does things like reading Old Norse sagas in the original tongue to pick out tidbits on ancient Viking wool dyeing, spinning, and weaving.

So, I grew up in a very resourceful and creative “maker”-oriented environment: I did pen and ink drawing and sculpture; I learned to work on cars, solder electronics, and hang sheet rock; I learned how to build and make things. And that creativity and tenacity to figure out how to make things still influences how I approach many things, even if these days it involves a multidimensional dataset, or a homebrew sensor built with a Raspberry Pi.

Q: Do you consider yourself a geohipster? Why / why not?

A: We grizzled geohipster silverbacks might be tempted to say something hipsterish like “I was geo before geo went mainstream,” but one look at me and you’d probably think more geohippie than geohipster. I don’t possess any colorful skinny jeans (not that I’d fit into skinny jeans), I don’t wear Vans or ironic t-shirts under a blazer. My natural state is more likely to involve hiking boots and a tie-dye. But hipster jokes aside, it’s actually what’s on the inside that makes one a geohipster. It’s about out-of-the box thinking, being creative, passionate and innovative, and weaving together a lot of different knowledge and experience into your work.

Q: On closing, any words of wisdom for our global readership?

A: For one thing, remember that Venn diagram of things you enjoy / things you are good at / things you can get paid for. I’ve found that many of the most satisfied, creative and talented folks I’ve met in geo were multidisciplinarians. Some came into geo from another field, some were folks who started in geo but who then did a deep dive into another field. I also think that shows that we need to mix it up, keep thinking outside of the box and looking across the sciences.

Don’t get too hung up on specific tools and technologies or stay in your comfort zone. Instead, get comfortable being uncomfortable, get outside of your comfort zone, and stay curious. Keep learning. Focus on outcomes, keep adding new techniques and approaches to your toolbox, and apply your knowledge to a wider variety of problems.

Don’t be afraid to learn to code — it can make your life easier through automation, overcoming limitations of boxed software, or wrangling data. You don’t need to be an expert coder, often just a smattering of skills and googling code snippets will get you there. Though I’ve hacked around with over a dozen languages, these days I mostly use SQL, Python, JavaScript, R, and some shell scripting to get things done.

And, get involved in your local geo and tech community. Here in the nation’s capital we are particularly blessed to have a number of great geo and techie Meetup groups like Geo DC, always bringing new presentations and insights and great networking over beer – but even if you don’t have a strong local geo and tech community, there’s a strong and vibrant online geo community on twitter and social media.

Comments

One response to “Dave Smith: “Many of the most satisfied, creative and talented folks I’ve met in geo were multidisciplinarians””

[…] http://www.geohipster.com/2017/05/16/dave-smith-many-satisfied-creative-talented-folks-ive-met-geo-multi… […]